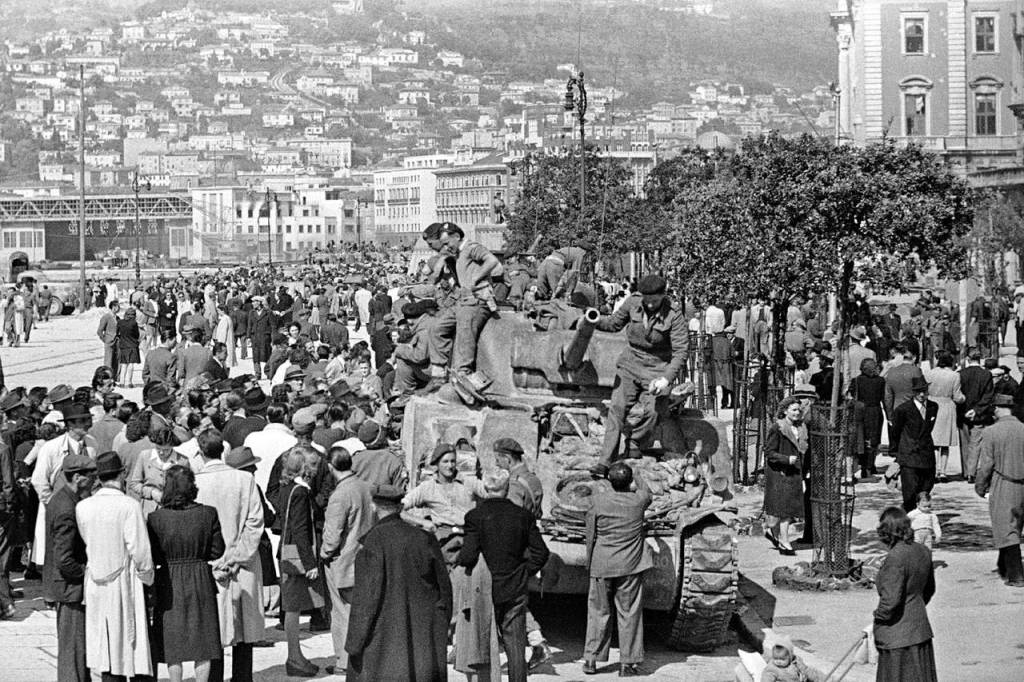

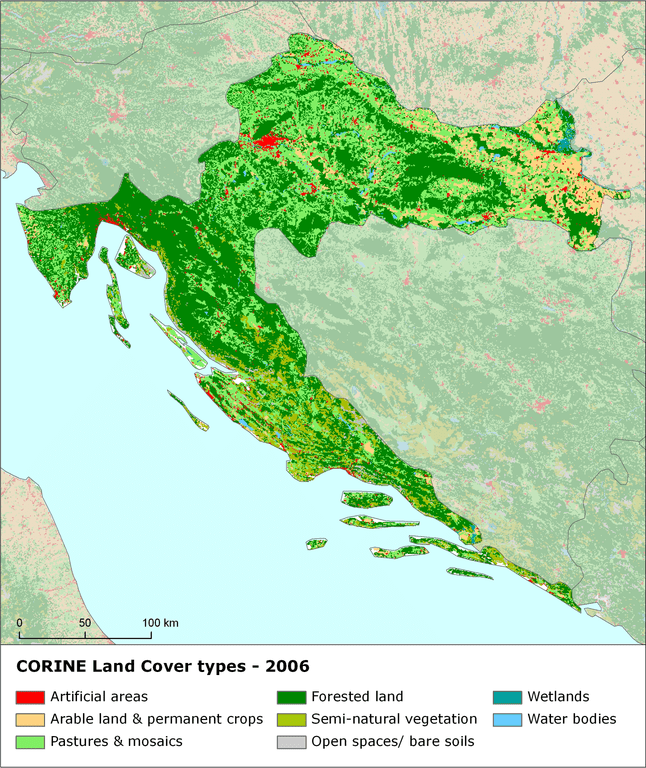

As the 2026 Winter Olympic Games in Milano closed–and while the Paralympics Winter Games are happening–I recalled the 1984 Winter Games in Sarajevo whose theme was peace, unity and cultural identity.2 Brilliant campaigns by tourist organizations helped to make the games a success. 250,000 people visited the games over 12 days, with 50,000 attending the opening ceremonies. I was one of 2 billion watching the games on television.3 Unlike the well-known 2026 Italian host sites, the vibrant cultures and physical beauty of Sarajevo was a revelation to many. Nestled in the Dynamic Alps, Sarajevo was then the capital of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, one of the six republics that comprised the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. By 1991 the country of Yugoslavia had disintegrated and Sarajevo was at the center of a civil war. Slovenia was involved for 10 days before the Yugoslav Army withdrew peacefully, but there was no peace in five former republics–Serbia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro and Bosnia Herzegovina–until 1995. War ravaged countryside and cities; Vukovar, Dubrovnik, Split, Zagreb, Belgrade, Srebrenica. Sarajevo endured a 44 month siege from April 5, 1992-February 29, 1996. 11,500 people were killed. The city and Olympic spirit were devastated.

Many books have been written about Sarajevo and what has been variously called: the Balkan War, Yugoslav Wars, Homeland War, 90s War and War of Independence. Zlata’s Diary by Zlata Filipović, a firsthand account of the Sarajevo siege, and Girl at War by author and translator Sara Nović were accounts that shaped my understanding of the breaking apart of Yugoslavia. Two historical fictions published ten years apart written by Canadian authors who both lived in British Columbia are based on Smailović’s playing his cello amid ruins. They share a mission to promote peace. One was a series of linked stories written in a documentary style for adults, and the other children’s book with illustrations featuring peace doves by visual artist Deryk Houston.

Who was Vedran Smailović? He was the principal cellist for the Sarajevo Opera, Sarajevo Philharmonic Orchestra, the Symphony Orchestra RTVSarajevo and the National Theater of Sarajevo respectively for many for decades. The image of Smailović playing his cello in the midst of war in June 1992 became a global symbol of peace. His motivation? Smailović is quoted in Echoes from the Square as saying, ‘Music is the love that connects people. My wish is for everybody to be able to share this.’ A pointed response to the devastation he witnessed in his hometown and country. The composition Smailovic played is often referred to as “Albinoni’s Adagio” or “Adagio in G minor by Albinoni, arranged by Giazotto. ” In an eerie parallel to Sarajevos destruction, most of Albinoni’s work composed in the early 1700s was destroyed in WWII. Giazotto obtained a manuscript fragment from a slow second movement of a church sonata shortly after WWII. This fragment was found in a Dresden library which preserved this collection even though the library buildings were destroyed in bombing raids in February and March 1945.

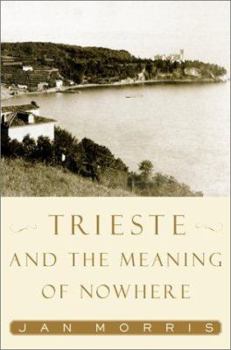

I first read Steven Galloway’s award-winning The Cellist of Sarajevo four or five years after it was published in 2008. This book contextualizes the iconic image of Smailović playing his cello on a bombed out street from three perspectives. University professor Galloway is a skilled writer who used Smailović’s action as a device to write about the war from three different perspectives. He did not name Smailović, nor did he consult with Smailović about his book, which struck me as odd because Galloway conducted quite a few interviews to craft his characters.

Published in 1998, Echoes from the Square by Elizabeth Wellburn was not only written with Smailović’s consent, in her narrative, his voice describes the event that killed innocent people on his street to a young aspiring violinist named Alen. Echoes from the Square is a serious children’s book with a hopeful message. Hear Wellburn reading Echoes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wMrf_sd3gkA

Wellburn’s young protagonist Alen contrasts with Galloway’s Arrow, a 20 year old countersniper, who was coerced into protecting Smailović by a Yugoslav Army faction. Her narrative and that of two Sarajevan men contain dialog and remarkable descriptions of desperate attempts by their neighbors as they crossed bridges and streets under sniper fire to obtain drinking water and food for their families who were literally starving. Enter Smailović. Given Galloway’s book’s title, the shadowy presence of Smailović who is found only in the first five pages, was a bit misleading. What was clearly spelled out was Arrow’s assessment of war, leaving readers’ with powerful, simple antidote. Arrow, ostensibly speaking for Galloway, ends her narrative reflecting, “She didn’t have to be filled with hatred. The music demanded that she remember this, that she know with certainty that the world still held the capacity for goodness.”

The publication of The Cellist of Sarajevo enraged Smailović whose image Galloway used without permission, and then later withdrew from the book’s cover. Smailović also offered this corrective, “I didn’t play for 22 days, I played all my life in Sarajevo and for the two years of the siege each and every day…They keep saying I played at four in the afternoon, but the explosion was at ten in the morning and I am not stupid, I wasn’t looking to get shot by snipers so I varied my routine.”4 Smailović and the siege were featured in a June 8, 1992 New York Times article by John F. Burns titled, “The Death of a City: Elegy for Sarajevo,” that was part of a Special Report: A People Under Artillery Fire Manage to Retain Humanity. This journalism showed how Smailović created a site of memory through his actions that inspired others; Sarajevo Roses street memorial, photography, musical compositions and concerts, books and documentary films.

Author Galloway was astonished and upset at Smailović’s reaction. Galloway responded by saying, “The problem is that Mr Smailović took a cello on to a street in a war and that’s an extremely public act. I can’t ignore that as an artist…I’m at a bit of a loss to know how to address it. I don’t think that I crossed any lines about writing fictional things about a living person. I got most of my stuff off the internet.”6 Galloway told NBC news, “The cellist in my book is based on a real character. He doesn’t ever speak in the book. I was kind of careful not to put words, I don’t want to put words in his mouth.” 7

In the words of one of Galloway’s characters, Dragan, “There is no way to tell which version of the truth is a lie.” This cynical assessment accurately describes the political circumstances Galloway is depicting, where fairness, honesty and respect for others doesn’t count for much. Later Galloway and Smailović reconciled in Ireland due in part to Derek Houston’s intercession.

Nedžad Abdija, Ismet Ašćerić, Ruždija Bektešević, Snježana Biloš, Predrag Bogdanović, Vladimir Bogunović, Vasva Čengić, Gordana Čeklić, Mirsad Fazlagić, Emina Karamustafić, Mediha Omerović, Bahrija Pilav, Mila Ruždić, Mile Ružić, Hatidža Salić, Galib Sinotic, Abdulah Sarajlić, Sulejman Sarajlić, Sreten Stamenović, Srećko Šiklić, Božica Trajeri – Pataki, Vlatko Tanacković, Srećko Tanasković, Tamara Vejzagić – Kostić, Jusuf Vladović and Izudin Zukić.

Killed in a Bread Line: 33 Years Since the Ferhadija Massacre

The Sarajevo Times May 27, 20258

The viciousness of war can inspire impassioned pleas for peace. Tourism with the intention to learn and remember are not the same as travel to war zones where adrenaline rushes and personal experience at the expense of others prevail. How can tourism build on Smailović’s legacy to contribute to peace? Museums of remembrance of the war such as the acclaimed Children of War Museum Exhibit9 attract and educate visitors. Tours created with the intention to promote peace transcends war tourism’s dark side.10 In 2011 Bosnian Voyager Tours11 of remembrance call out the horrors of war and war profiteering with cautionary stories. Likewise another unique, powerful interpretation of the war in and on Sarajevo is provided by Viator tours titled ROSES OF SARAJEVO (War + Olympic + City) – Story of a Survivor.12 These tours are advertised as ‘The official war + olympic + city tour of Sarajevo, presented ONLY by the tour guides that survived the siege.’ Like many tours of its kind Viator Tours features and exploration of ‘The Tunnel of Hope nowadays is the most touristic and symbolic place of Sarajevo.’ Proclaiming ‘the ‘place that ended the 20th century,’ the tour also includes a trip to the gift shop. Of note is that the musician Sting participated in the tour in 2022, the same year he gave a concert in Sarajevo.

Artists who make music to de-escalate or protest aggression inspire each other. Peace activist and musician Joan Baez visited Sarajevo and met with Smailović. Distinguished British composer David Wilde wrote music protesting against the abuse of human rights including the solo cello piece The Cellist of Sarajevo (1992) dedicated to Smailović. virtuoso cellist Yo-Yo Ma and other artists went on to record Wilde’s composition. In 1993 Smailović immigrated to a small town outside of Belfast, Northern Ireland to escape the war. His collaboration with legendary Irish musicians Tommy Sands and Dolores Keane is one of many instances when like minded artists who have experienced war first hand create soulful sounds of peace.

https://www.8notes.com/discover/how-music-inspires-ukraine.asp

- https://balkaninsight.com/2024/02/08/winter-glory-sarajevans-bittersweet-memories-of-the-1984-olympics/ ↩︎

- ‘Sarajevo ’84 distinguished itself in various ways. It was the first modern Olympics unmarred by Cold War boycotts by either NATO or Warsaw Pact countries and boasted the highest-ever participation in terms of nations sending competitors.’ See footnote 1 from Balkan Insight ↩︎

- https://yugoblok.com/sarajevo-1984-winter-olympics/ ↩︎

- See David Sharrok’s June 7, 2008 The Sunday Times article,” Cellist of Sarajevo Vedran Smailović is Wounded by Words.” https://www.thetimes.com/travel/destinations/uk-travel/northern-ireland-travel/cellist-of-sarajevo-vedran-smailovic-is-wounded-by-words- ↩︎

- https://sarajevotimes.com/sarajevo-rose-in-ferhadija-street-finally-restored/ ↩︎

- David Sharrok’s June 7, 2008 The Sunday Times,”Cellist of Sarajevo Vedran Smailovic is Wounded Words,” https://www.thetimes.com/travel/destinations/uk-travel/northern-ireland-travel/cellist-of-sarajevo-vedran-smailovic-is-wounded-by-words-9. ↩︎

- High Plains Public Radio Reader’s Book Club, January 13, 2023 “Vedran–the Cellist,” by Mike Strong, https://www.hppr.org/2023-01-13/vedran-the-cellist ↩︎

- https://sarajevotimes.com/killed-in-a-bread-line-33-years-since-the-ferhadija-massacre/ ↩︎

- https://warchildhood.org/global-collection/ ↩︎

- During the 1990s was a cruel, gruesome version of war tourism allegedly took place during the siege of Sarajevo, when for a price, wealthy foreign tourists were allowed to join Serbian Army snipers in organized killing sprees of Sarajevans called human safaris. Many news outlets including BBC, Al-Jazeera, CNN, DW and others report ongoing investigations. ↩︎

- https://bosnianvoyager.com/tour/sarajevo-siege-tour-war-tunnel-1992-1996/ ↩︎

- https://www.viator.com/tours/Sarajevo/Roses-of-Sarajevo-Sarajevo-siege-tour/ ↩︎