Trieste and The Meaning of Nowhere was Welsh-born author Jan Morris’s last book. Morris, who did not like to be called a travel writer, provides an explanation of her memories, and maybe of all travel writing, as ‘a little book of self-description.’ It is a lively, personal, interpretation of a city over time, reminiscent of lingering conversations over coffee. This is a hallmark of Morris’s Trieste and of Trieste itself, which like Vienna, had and still has, a thriving cafe culture that supported writers. In 1933 Francesco Illy founded Illy coffee in Trieste https://www.illy.com/en-ww/illy-caffe-history and accidentally, the beginnings of literary tourism. Paul Clemens 2001 review for The Guardian calls Morris’ Trieste ‘neither guide book, travel memoir, nor a chronological history but is a relaxing, reflective essay written from a personal perspective by someone who clearly knows the place well and is attuned to its history.’ Morris captures the feeling of Trieste as she knew it with, ‘Melancholy is the city’s chief rapture.’ In Trieste Morris adopts a wistful tone that pervades this once economically and politically strategic Mediterranean port.

https://www.theflorentine.net/2025/01/08/fotografia-wulz-trieste/#google_vignette

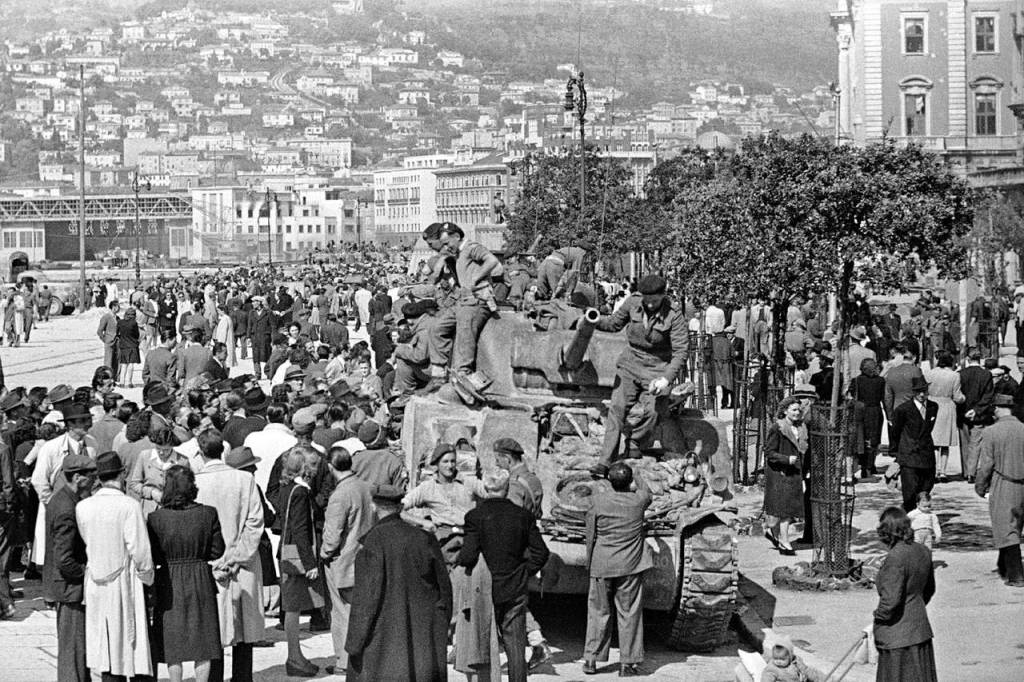

Jan was posted to Trieste during WWII as James Morris, one of the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers and a regimental intelligence officer. Her WWII service influenced her perception of Trieste, but more interesting are parallels between Morris’s own identity formation and the many changes in and to Trieste throughout the 19c and 20c. In Trieste, Morris describes first experiencing the city as a young military man who was not a published author, not a public figure, unmarried, and not yet a father. Morris describes her engagement with Trieste in 2000 as an old woman, parent, grandmother, devoted partner, and civilian who was a widely recognized expert and author on travel in cities. Bridging cultural-generational divides is one way of looking at Morris’s Trieste, another is the way in which the city welcomes—or tolerates—outsiders.

When she began her transition in 1964, Jan was already a distinguished journalist and adventurer. She was the first journalist to climb Mount Everest in 1953 with Edmund Hillary and Tensing Norgay. Jan’s anthropological research of cities, notably; Venice, Oxford, Hong Kong, New York City (Manhattan) and Trieste mark her as a historian who values human connections. Like Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, Trieste and The Meaning of Nowhere, describes the zeitgeist and multiple identities of what are sometimes referred to as the Balkans—places seen as outposts by those who did not care so much about those places and the people who lived there as West and Morris did. West often praised Morris and seemed irritated by her success in a somewhat snarky 1974 New York Times review of Morris’s Conundrum which documents her gender-reassignment (then called sex-change). https://www.nytimes.com/1974/04/14/archives/conundrum-by-jan-morris-a-helen-and-kurt-wolff-book-174-pp-new-york.htm

Morris’s Trieste traces the history of a city with a confounding past. It was often hard to pin down who was in charge. Trieste has been governed by Venetians, Ottomans, Austrians/Hapsburg’s, post-WWII Western Alliances, Yugoslavs, Slovenes and again as in the past, Italians. Those transitions helped this multi-level town framed by the Adriatic, cradled by mountain forests and carved from karst to assume multiple, if murky identities. It is a transitory place one wanders into coming from and going to somewhere else. Morris draws on the geopolitical tenet, geography is destiny1 and her Trieste gives vibes similar to Joyce’s description of Trieste as ‘bittersweet, it is a wounded city like Dublin.’ Both Joyce and Morris express an affinity with the Triestini, whose identity, like their own was often in flux. Joyce’s literary reputation was undoubtably known to Morris. Joyce left Dublin for Trieste in 1905 to teach at the Berlitz School. After a short detour in Pula which was deporting foreigners at the time, Joyce returned to Trieste to teach at Berlitz. While in Trieste Joyce completed Dubliners, an autobiographical collection of short stories, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, poetry, a theater play and the first three chapters of his most famous novel, Ulysses. Trieste was the city where he matured as a writer (frequenting taverns and brothels) and called home until 1920.

Joyce began an important friendship with Triestino Italo Svevo (born Aron/Ettore Schmitz) when they met in London. There the wealthy Svevo, a businessman, and erstwhile writer hired the impoverished Joyce to tutor him in English—other influential clients followed. Svevo is thought to be the inspiration for Leopold Bloom inUlysses. Svevo’s wife, Livia Veneziani, whose hair Joyce describes as a river, inspired a character in Finnegans Wake. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/italo-svevo. When Joyce returned to Trieste 1919, the Mussolini-led government provoked his move to Paris. He did not come back to Trieste. Today’s Trieste has a hotel, trail and museum devoted to Joyce. https://museojoycetrieste.it/en/history-of-the-museum/

The tone of Morris’s Trieste echoes another influential writer of the early 20c, poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Rilke began writing the Duino Elegies in 1912 while holed up (by invitation) at the Castle Duino 33 kilometers north of Trieste. Rilke’s Duino Elegies were completed in 1922 after his WWI military service. His poetry foreshadows the existential crises that pervaded Europe following two World Wars and expresses how spirituality and the natural world give meaning to everyday life in ways that religion did not. It’s hard to believe Rilke did not influence Joyce and Morris.

Castello di Duino formerly the home of German Prince Alexander von Thurn und Taxis and Czech Princess Marie, and Castello di Miramare built by Archduke Maximillian of Austria are 15 kilometers apart. Travel south from Miramare along the coast Gulf of Trieste and you will arrive in Trieste in less than an hour. The Rilke Trail is another story.

So how did the convergence of these writers impact Trieste? I’m not sure they did, and that may be one of Morris’ points. She suggests the city gave writers the space and freedom of a blank canvas with tragic undertones. During WWII the San Sabba Rice Mills were transformed into the only death camps in Italy. https://risierasansabba.it/san-sabba-rice-mill-national-monument-and-museum/ After WWII Trieste became a refugee camp for Italians fleeing Communists who took over Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia. The city was declared a Free Territory in Article 21 of the Treaty of Paris, but that designation did not mean peaceful. Trieste was divided into antagonistic Italian and Yugoslav areas. Although considered de-militarized and neutral Trieste, retained the psychological and socio-economic trauma of war. Morris wades with precision into this morass as he documents a time when to some, Trieste represented refuge and freedom, to others uncertainty and cruelty.

Even with Morris’s skillful observations it is hard to find a cohesive sense of Trieste’s identity. In 2006 my daughter related that getting there from Pula along the coast was tricky because of the many highways. She never felt like she cracked into the real Trieste. So what is the real Trieste? My experience in 2014 was colored by the fatigue, apprehension and preferences of my travel partner. Like Morris, no nostalgic yearnings there. I found Trieste moody, sparkling and a bit forlorn. It took me a while to figure out why Piazza Unita d’Italia seemed like it was missing something. It’s the only square in Italy without a cathedral.

Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Does Trieste welcome visitors more or less than other cities? How can we know? From the standpoint of tourism studies, a single person’s experience over time, even those of an expert observer, has limited value. Eco (economic and ecological) perspectives would likely find Morris’s lack of quantitative data that sustainable tourism (industry and practitioners) rely upon to create policy, a weakness of his analysis. I guess it might be tempting to pigeonhole Morris as a time bound memoirist, wallowing in the heyday of the world’s cities. Morris counters irrelevance by calling out travel blogs and vlogs in 2000 as they began to dominate a fading genre but booming industry. She also calls out guidebooks, from Baedeker’s to Lonely Planet as facile introductions based on cursory understandings that helped to created the tourism as we know it today. Morris is not concerned with accumulating consumptive experiences as she is with the ways places effect the inner workings of her heart and mind.

Why did Morris feel compelled to describe cities? Where did she feel at home? In her descriptions and witty exchanges Morris tells us that deeply felt connections are entry points into self-discovery. As a child she knew she was living in a body where her true self didn’t belong. Maybe that is why she began searching landscapes for hidden meanings. Karst—harsh, full of secrets and an important morphic feature of Trieste’s history—was cited by Morris as elemental to the city’s character. Morris’s describes the setting for his swan song, a ‘hallucinatory city’ appreciated by those who are intrigued with its chimerical identities and who value ‘kindness, the ruling principle of nowhere!’ Morris’s passion was to share his understanding of gloriously complex places and the people who live there. It is curious that the last of her 40 plus books is far from where she ended up retiring—going home—to rural Wales.

For more Trieste see Daniel Scheffler 9 December 2025 excellent Substack article https://withoutmaps.substack.com/p/trieste-and-the-meaning-of-nowhere

- Geography is destiny recently re-examined by Ethiopian-American author Abraham Verghese MD, and Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky whose works are worth checking out. ↩︎