We travel to find ourselves and to lose ourselves, to open our hearts and eyes, to learn more about the world, to experience hardship, and to see the world clearly while feeling it truly.~ Pico Iyer

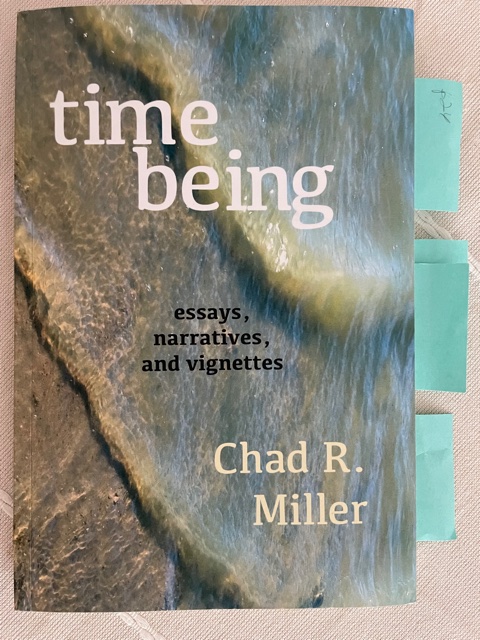

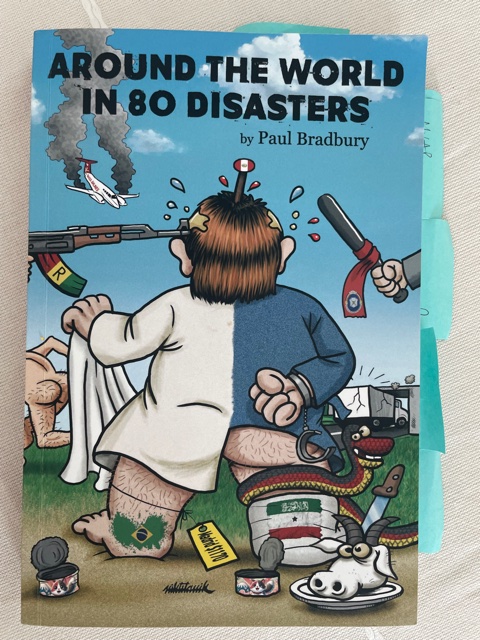

I recently read American writer and Peace Corps volunteer Chad Miller’s Time Being: Essays, Narratives and Vignettes alongside British expat, journalist, storyteller and media expert Paul Bradbury’s Around the World in 80 Disasters to learn more about tourism in Croatia and the former Yugoslavia. Admittedly this is a fairly narrow focus, but Bradbury’s and Miller’s musings about how travel has changed over the past 25 years before cell phones, Trip Advisor and booking.com provide valuable insights into the impact of those developments on Croatian tourism and travel generally. Both authors mourn the loss of freedom that past modes of travel granted even as they acknowledge the convenience technology brings. In his introduction Bradbury says ‘Around the World in 80 Disasters is my ode to a world of travel that has all but been lost, a collection of disasters which are all my own.’ Reading Miller’s beautifully crafted essays in tandem with Bradbury’s fly-by-the seat of his pants diary entries brought up what feels like an almost outdated debate about the difference between travel as transformative—think pilgrimage—and tourism as accumulative—think bucket list. Bradbury’s memoir, like his personal and professional life, centers on Croatia. Miller’s insights about Europe, the Horn of Africa where he and Bradbury separate but equally intense experiences are definitely worthy of consideration.1

Bradbury has an extensive online presence. Miller has an MFA in writing. He describes this book as Creative Nonfiction or Literary Nonfiction. It was written over two decades. Bradbury covers many decades of experience but wrote his memoir in two weeks. That being said, they share perspectives about a touristic search for ‘authenticity’, and structure their memoirs not chronologically, but by place. Bradbury casually asks questions such as, ‘How is the Adriatic coast different from the Mediterranean coast? Miller’s inquiries are explorations of the intersections between ‘time, place and movement.’ Both authors claim that human relationships are paramount, and I think both would agree with historian David Glassberg’s assertion that ‘places are not interchangeable with other places.’ Bradbury and Miller take this further saying places are not interchangeable with their former identities.

Ever the entrepreneur, Bradbury’s self-published volume follows a number of self-published books including Lebanese Nuns Don’t Sing (2013) in which he describes why and how he re-started his life after a divorce blind-sided him. Most of his disasters are consist of Bradbury naively trying to broker shady, ad hoc real estate or under-the-table governmental deals. Miller’s travels as a seeker of cultural understanding and as a Peace Corps volunteer have a more academic tone. But both memoirs have a funny-ironic connection to Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love as both use travel to help process life-changing personal events. Miller travels as an antidote to career disillusionment, and for Bradbury hitchhiking from the UK to South Africa was a way of dealing with the emotional fallout of divorce. Croatia represents a milestone where both of their lives are permanently changed.

Bradbury’s wanderlust culminates in finding home on Hvar. He met his wife, married, had children, learned the language and started a business. He is fully committed to promoting Croatia, hardly traveling in 20 years after he permanently moved to Croatia in 2002.

Miller describes a return to Split in 2014 after 40 years. On this trip Miller tried to access a version of his past self—time traveling to 1984 when he first visited and fell in love with Split where he began a life-long love of travel. Today he reflects that, ’People like me on some technical, semantic level, are refugees. We don’t feel at home where we belong, and we don’t belong where we feel at home. We feel strangely content when we’re estranged.’ See Yugoblok Travel Quests conversation between Peter Korshak and Miller. for more on Miller’s philosophy of travel.

Miller was and is charmed by Croatia’s beauty, and its complex, often confounding history. In Split in 2014 he felt this way, ’My beach, (Firule) my cove, my mountain, etc. stirs up a nostaglic yearning for an unchanging place of calm and peace.’ Today Miller admits, ‘Back then I was in a different frame of mind. Now my perspective has changed. I don’t want to live in Split with regular access to Firule. I do want to return to that beach, my secret beach, in the future. Meanwhile even if I can’t get back there, it’s kept safe as the beach of my dreams.’

photo-by-ivett

Following a grueling UN stint in post-genocidal Rwanda, Bradbury sips a gin and tonic in Somaliland while watching CNN. An advert for Croatia: The Mediterranean as it Once Was appears and he impulsively decides to buy a stone house with no heating, no sewerage or gas connection, or address on the island of Hvar. Upon arrival many of his questions to locals were met with derisive, incredulous laughter. When Bradbury learns that the internet cafe he depends on for his livelihood closes from October to May, along with most business on the island, he is confronted with the realities of living in a tourist-based economy. As a journalist, ‘spotty’ internet connection on Hvar was an obstacle Bradbury not only overcame, but triumphed over when he founded the online news source, Total Croatia News. Bradbury’s assertion that the experience of travel has been dulled by the many online resources is somewhat ironic considering his livelihood and success is built on the technology he names as the culprit. In the past five years, Bradury has followed, written about and endorsed Zagreb as a digital nomad destination, recently issuing digital nomad visas. In another ironic memory after the 2008 global economic crash, Bradbury notes that British and Irish buyers ‘were going crazy for coastal property in Croatia.’ In the same period Bradbury’s adventures in real estate contradicts stories about thorny relationships between Croatians and Albanians. See How to Walk Out of Life and Start Again http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XodJZrToZLMhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XodJZrToZLM at 33 | Paul Bradbury | TEDxVirovitica Library, 2024

Around the World in 80 Disasters works as a parody of French author Jules Verne’s 1873 adventure novel. Bradbury’s reminiscences are fresh and funny, beginning in the late 1990s with ‘No plan, no agenda except to travel.’ Serendipitously obtaining NGO and government positions because of his language skills (mostly Russian fluency), a willingness to accept posts others might not, and ability to drink large amounts liquor, Bradbury’s disasters/escapades are blessings in disguise partly because he survives them. If he had been a woman I’m not sure if that would have been the outcome. Thankfully, in 2025 there have been changes.

Drinking liquor—beer, vodka, rakija—plays an important role in Bradbury’s life. Often associated with Croatian ways of doing business and expressing hospitality, his fondness and capacity opened doors and allowed him to gain local trust in Russia, Croatia and across Eastern Europe. Gaining trust came to Miller over coffee. Miller has an epiphany while in Ethiopia partaking in ‘shaibunna, the Ethiopian tradition of a long morning break with coffee, tea, snacks and chatting with friends, colleagues, and anyone else who happens to be sharing the same physical space.’ I imagine Bradbury had a revelation or two while Ćakula na kavi/talking over coffee–a mainstay of Croatian life. Because embracing local culture is central to both authors view of travel, I wonder what they would make of the new conceptual traveling exhibition/Fjaka Museum.

If Miller and Bradbury sat down over a coffee or pint what might we learn about Croatia over the past thirty years? Imagining a dialog between these two accomplished storytellers would likely show a lot of overlap. Their memories are sentimental, self-aware, with not a lot of talk about climate change but with implications that travel today needs to be purposeful and of benefit to the places visited. A core eco-tourism question— If your impact on a place is not beneficial to the place can it be beneficial to you?—is one that might come up. Miller first visited Dubrovnik in 1979, only five years after UNESCO designated its Old Town a World Heritage Site, and before the collapse of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Today his view is that ‘Dubrovnik like the rest of Croatia, is on a tourism sugar high and bound to crash eventually.’ In spite of a self-guided Sweet Tooth Map of Dubrovnik that he and his wife Jen happily enjoyed, Miller cautions, ‘too much tourism is eating the heart out of Dubrovnik.’ Anti-tourism protests in EU cities validate his concern.

Like all memoirs, Bradbury’s and Miller’s look back at how the past shapes present realities. Their travel memories reminded me of historian Eric Zuelow’s thoughts on travel and identity, “The lens through which we see our age are as much a product of our time as a our ancestor’s where a product of theirs. Looking at the story of tourism as it played out over hundreds of years illustrates this point very nicely. It makes it possible for us to see things we take for granted—that beaches and mountains are beautiful for example—are the outcome of many factors that are contingent. This is not simply a question of what tourists do or what they see….Studying the past obviously teaches us about the past—but it can also tell us a tremendous amount about ourselves—if we learn the lessons of context.” Whether in Croatia or elsewhere, Bradbury’s and Miller’s travel stories are told with wit, self-effacing humor and enough reflective insights to create thoughtful, engaging armchair travel.

Wikipedia

- Miller and his wife were deeply affected by their time in Ethiopia. A hallmark of Miller’s experience is grappling with the imagined and the real. ‘A local place name (Makaraka) not actually attached to any one place and not having an identifiable, marked place on a map symbolizes places ‘burn on in my unconscious until the end of my days precisely because I could never reach them, could never touch them, could never walk upon them. Inaccessibility was the very essence of their allure, and indeed indefinability was at the core of their very nature…’ Time Being: Essays, Narratives and Vignettes. ↩︎