Edited by Town Mayor, Poet, and Musician Riccardo Staraj, Novi Vinodolski. 2012

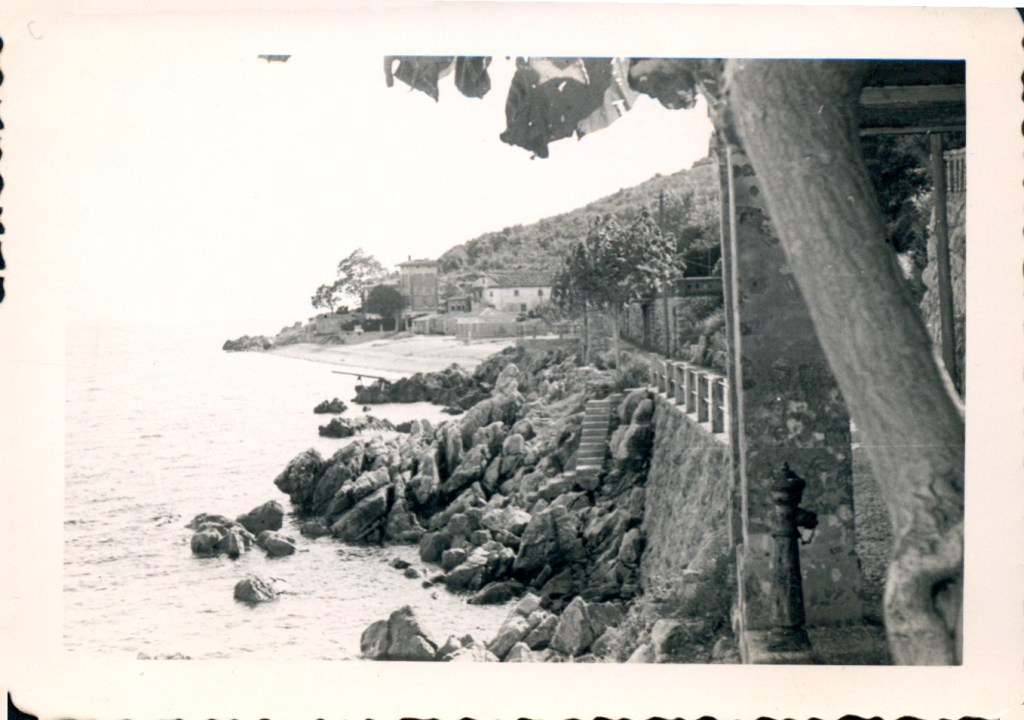

The photograph seen above was taken almost 100 years ago. In 1945 JNA/Yugoslav People’s Army units disembarked on the waterfront of Mošćenikča Draga. Heavy military equipment may have run into this now phantom bridge which like Yugoslavia, doesn’t exist today. However an intriguing linguistic connection to Mošćenikča Draga and Moščeniče is possible. In his 2012 essay, Cultural Historical Heritage of the Community of Mošćenićka Draga, journalist Goran Moravček writes, ‘Some people derive the name of the settlement Moščeniče from the Croatian word ‘most’ meaning bridge.’ The bridge’s arch and architectural detail suggest diverse cultural influences, and the 1927 photo shows it was popular with the locals.

The little Bridge in Opatija connects a concrete pavilion to the lungomare. Opatija’s first bathing pavilion was built in 1896 and was an instant attraction for tourists and locals.

https://hr-cro.com/croatia/opatija_plaza_slatina/eng

Photo, Mary Martincic Scatena, 1952

Not exactly a bridge, but this short, scenic walk bridges Mošćenička Draga’s two heavily touristed beaches, Sipar and Sveti Ivan.

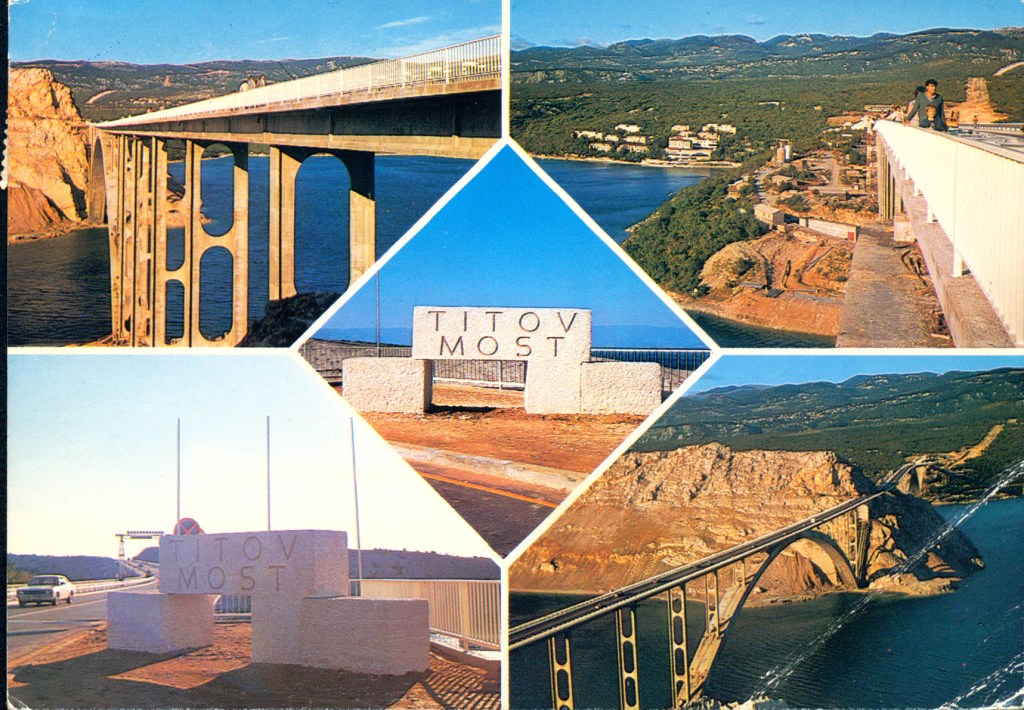

This 1980s postcard proudly displays TITOV MOST. The bridge is now called Krk Bridge and connects Krk to mainland Croatia. Since his death in 1980 debates about the consequences of Josef Broz Tito’s policies in the former Yugoslavia likely contributed to the name change. Krk is approximately the same size as nearby Cres. They are Croatia’s largest islands with very different physical shapes and distinct ecosystems and cultural identities.

Watercolor by Redditor u/qatya, Redditor

Stari Kameni Most (Old Stone Bridge) over the Dubračina river is in the center of Crikvenica, a popular resort on the Kvarner Riviera. Crikvenica is 34km south of Rijeka.

Crikvenica’s White Bridge is near Crkva Uznesenja Blažene Djevice Marije, (Church of the Assumption of Blessed Virgin Mary). It gracefully arches over the Dubračina River. Crikvenica has a similarly arched red bridge over the Dubračina that’s also pedestrian only.

The islands of Lošinj and Cres were once one island called Apsyrtides. Empire building Romans dug a narrow channel to shorten travel times to the south. Today these islands are connected by a swing bridge that opens over a strait that spans 12m/39ft. Since there is no road connecting the islands to the mainland, visitors and locals must take ferries or other water craft.

Stari Most captured journalist Rebecca West’s imagination as she traveled in the former Yugoslavia during the 1930s while researching her 1,181 page epic Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. West saw Stari Most as a motif for transcending barriers and connecting cultures. It was built from 1557 to 1566 by architect Mimar Hajrudin. For centuries it functioned as a crossroads between the city of Mostar’s Muslim Ottoman and Christian Slavic worlds. Not unlike Sarajevo, the city of Mostar was composed of different neighborhoods with well-defined ethnic groups who lived harmoniously. The bridge facilitated all kinds of exchanges, from merchant trading to lover’s trysts.

Stari Most survived WWII’s heavy tank and artillery traffic, but on November 9, 1993, during the 1990s war, Stari Most capitulated to Croatian shelling and fell into the Neretva River. Four months after its destruction there were calls for Stari Most to be rebuilt. The 12.5 million euro reconstruction of Mostar’s Bridge was funded by the World Bank, local government, Italy, the Netherlands, Croatia and The Council of Europe Development Bank. UNESCO oversaw the project. Stari Most was rebuilt identically to the original, using the same building materials and techniques as were used in 1566. Stones were pulled from the Neretva, local quarries were contracted and traditional stone-cutting schools were brought in. Opening celebrations took place on July 23, 2004 with foreign leaders touting the bridge as a symbol of reconciliation. Today the bridge is a major tourist attraction, and for some it signifies peaceful co-existence. But mass tourism does not necessarily promote cultural understanding, and is not usually compatible with serenity.

So, when you walk upon the stone

do not take for granted

Something new to you

is something deeply enchanted

excerpt from The Secret Gem by Katarina Bučić

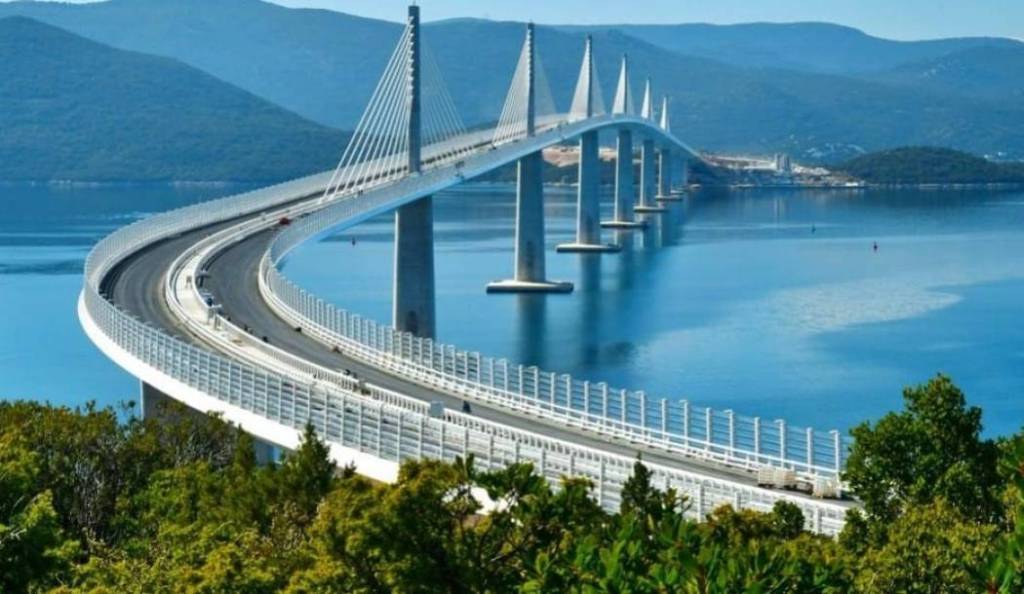

On July 26, 2022 Croatia officially opened the Peljesac Bridge/Pelječki Most. One of the largest EU funded infrastructure projects in Europe, the Peljesac Bridge connects two parts of Croatia’s Adriatic coast across 9km of Bosnian territory. It makes access from Split to Dubrovnik — thanks to its UNESCO World Heritage Site designation and Game of Thrones, Croatia’s biggest tourist attraction today — much quicker and eliminates border crossings. During the summer tourist season, more than 12,000 vehicles each day drive across the bridge and local residents indicate that it has a significant impact on the one-day visitors’ and weekend demand. The strikingly designed cable-stayed bridge is 2.4km long. It was built by a Chinese firm which completed the project on schedule in four years despite complicated engineering, controversies with Bosnia-Herzegovina and covid restrictions.

Pelječki Most is good for Croatian trade and tourism, but what is its impact on the marine conservation area it spans? In 2015 the independent research institute OIKON Ltd, Institute of Applied Ecology, presented data showing the bridge would not have a negative effect on the protected mussel and oyster beds in the Bay of Mali Ston. This area is habitat for a total of 89 species of shellfish which thrive in the bay’s mix of salty Adriatic and fresh Neretva and submarine spring waters. Exporting shellfish (only mussels and oysters are farmed) is big business. Marija Radić, President of the Shellfish Farmer’s Association in Ston agrees Pelječki Most will make transporting produce from the sea much easier. In 1927 Marija’s grandfather, Luko Maškarić built infrastructure to cultivate and harvest shellfish in Mali Ston Bay that is in still in use.

Ostrea Edulis/ European Flat Oysters have been cultivated around the Pelješac Pennisula before the time of the Roman Empire. Cultivation flourished under the Republic of Ragusa which produced the first written accounts of shellfish farming. Today some Mali Ston family farms use traditional wooden racks. Oysters take 18-24 months to mature and like mussels, are best eaten fresh from the water.

Sadly Mali Ston oyster and mussel production has not yet recovered from the drop in tourism due to Covid-19 travel restrictions. Because cooler water temperatures produce the most sought after oysters, the ‘season’–is months with the letter ‘r’–November through April. Held mid-March on Saint Joseph/Sveti Josip Day, Ston and Mali Ston’s Oyster Festival returned from a pandemic hiatus this year.

The Roman Bridge built of stone it is located at the entrance to the town of Beli on Cres. It is said to be 2000 years old. In Roman times Beli was known as Caput Insulae. An inscription in Beli indicates it was founded during the reign of Emperor Tiberius, AD 14 until 37. Evidence of an important Roman settlement include, the bridge, and the remains of a temple and a forum. The Roman Bridge is actually part of an ancient stone road that helped transport goods from the port inland. If bridges are markers of conquest and rule, this one has a durable pedigree.